The decline of area Black-owned farms in recent decades mirrors a national trend

Jamel Rahkeera leads the team at Village Family Farms that transformed abandoned plots of land into Cleveland’s first Black-owned and operated farm and farmers market. (Photo by Dianne Johnson and Yellow Springs News)

Only 193 of Ohio’s 77,805 farms are Black-owned, according to the USDA.

By Carol Simmons, Yellow Springs News

Sept. 17, 2020

“This whole road — from Cedarville to Wilberforce — used to be Black-owned farms,” fourth-generation farmer Paul Clemens III mused earlier this week.

He was speaking by phone, but you could still imagine Clemens, 43, extending his hand out toward Ohio Route 42, which runs along the 104-acre farm he works with his 73-year-old father, Paul Jr. The younger Clemens was taking a break from mending fences to talk about the property in eastern Greene County that’s been in his family since the early 1900s.

Now, although the local landscape remains mostly rural, the father and son are the only Black farmers they know in the area. And the USDA agricultural census, which gathers farm-related statistics every five years, missed them in its last count.

According to the agency’s latest census report, released in 2017, Greene County has no Black-owned farms, out of a total 617. Neither does Clark County, with 742 total farms; while Montgomery County charts nine Black-owned farming ventures of 782 farms overall.

Across Ohio’s 88 counties, which count a total of 77,805 farms statewide, 193 are Black-owned, according to the USDA.

Clemens’ observation that the numbers of area Black-owned farms has declined in recent decades matches the national statistics. From the early 1900s, when Clemens’ great-grandfather boasted holdings that included 160 acres and 100 head of cattle, until the early 2000s, Black farmers have declined in number from a high of 17% across the country to just over 1.5% nationwide, according to a report published last year by the Center for American Progress.

The dwindling numbers are worrisome to organizers of a 2020 conference in Yellow Springs that explored the history of Black farming, considered causes for its declining numbers, and explored new initiatives and resources for supporting Black-led agricultural activities.

Black Farming: Beyond “40 Acres and a Mule” was presented by the Arthur Morgan Institute for Community Solutions in September 2020. The two-day event included small-group tours of several agricultural programs at Central State University, online speakers, breakout sessions, networking and a resource fair. Antioch College and the Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center also were sponsors of the event.

Historical Precursors

Setting the historical record straight will be a focus of the conference’s opening. Organizers note that people of African descent have a long agricultural tradition in the U.S., in spite of their forced farm labor under chattel slavery. But that tradition is not well known.

Anna-Lisa Cox, a historian affiliated with Harvard University, gave the keynote address at the 2020 conference. She is the author of “The Bone and Sinew of the Land: America’s Forgotten Black Pioneers and the Struggle for Equality,” published in 2018.

The book documents the migration of Black settlers into the Northwest Territory (now Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois and Wisconsin), from the end of the Revolutionary War until the mid-1800s. Her research found a large Black rural population, most of them farmers, who were establishing successful homesteads and community centers throughout the early part of the new nation’s life. Their relationships with indigenous peoples were notably often more peaceful than those of European settlers as well.

Urban farming efforts in the state include Cleveland’s High Tunnel Initiative. High tunnels are steel-framed structures with removable heavy plastic sheets that are fitted over the frame. Avon Standard, right, was the first to apply to be part of the program. He’s pictured here with urban conservationist Al Norwood. (Yellow Springs News Photo submitted by Dianne Johnson)

Clemens’ own family history parallel’s Cox’s research. While he points to four generations of farmers in Greene County, he traces his Ohio heritage further back to James and Sophia Clemens, a formerly enslaved couple who came to southeastern Ohio from Virginia in the early 1800s. The pair helped establish the Longtown settlement near the Ohio-Indiana border, where Black and people of mixed race enjoyed a level of community standing and respect until the mid-century. It also became a documented stop on the Underground Railroad.

Cox’s book also documents how many of the Midwest’s early Black farmers were driven out by subsequent white settlers and progrssively discriminatory laws by the mid-1800s.

Antioch College Associate Professor of History and Vice Dean of Academic Affairs Kevin McGruder, who helped organize the Black farming conference, said that Cox’s work is an important scholarly and societal contribution.

“Black farmers of that time are not represented in the historical record as part of the pioneer class,” McGruder said in a phone interview earlier this week. Cox’s research is filling in that void.

He also noted that the agricultural history of Black people in the U.S. has primarily focused on the South, which then leaves out the lessons and models of life experiences in the rest of the country.

In a 2018 interview for her undergraduate alma mater, Hope College in Michigan, Cox said.

“These African American pioneers who came out to settle the frontier long before the Civil War are an integral part of our American past, but their history has been buried for far too long.”

“If we lose who helped settle the frontier, who was essential in these states’ histories, we lose a sense of who belongs,” she said.

Cox’s research “really gets at the core of what it means to be an American,” McGruder said.

McGruder said Black agricultural history after Emancipation and the end of the Civil War was also rich with experiences that have not been fully represented. Chattel slavery and sharecropping were not the only stories.

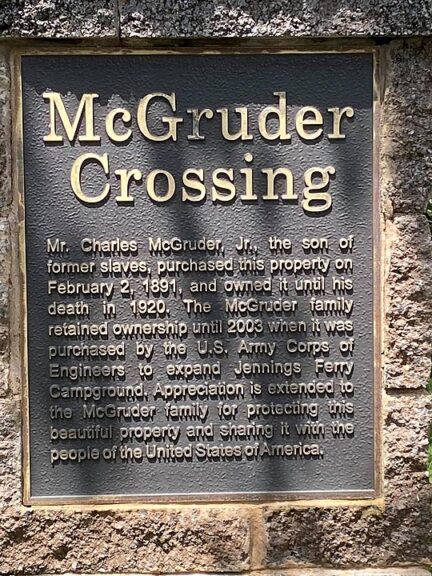

Historian Kevin McGruder’s family was honored with this plaque after selling acreage from the family farm in Alabama to the federal government. (Yellow Springs News Photo courtesy of Kevin McGruder)

Historian Kevin McGruder’s family was honored with this plaque after selling acreage from the family farm in Alabama to the federal government. (Yellow Springs News Photo courtesy of Kevin McGruder)

His own family has farming roots in Alabama, McGruder said, telling how a great-grandfather on his father’s side bought 300 acres in 1890, and the property has stayed in the family since that time.“

My father lived on the farm until he was 12,” McGruder said. “My father said of the Depression that they didn’t have a problem because they already did everything for themselves.”

Hanging onto the land has sometimes been tough, but the family has managed to do so for over 100 years, selling only 50 acres about 15 years ago to the federal government for public park land. The sale was commemorated in a plaque honoring the McGruder family (at right).

Hanging On

The loss of land holdings over time has been an issue for all farmers, but especially Black farmers, Terry Cosby, the Ohio head of the USDA’s Natural Resource Conservation department, said in a phone interview this week.

Based in Columbus, Cosby, too, can point to a personal heritage of farming. His family has a farm in Mississippi that goes back four generations.

“My great-grandfather, when he was freed in South Carolina, moved to Mississippi,” where he purchased a piece of land to farm, Cosby said.

The importance of that purchase remained strong for his family.

“My dad always told me, ‘If you’ve got land, you’ve always got somewhere you can go,” he said.

Cosby said that family farms were hard hit as agriculture became the business of larger, more industrial farming techniques and enterprises able to supply bigger stores and chains.

He also cited disinterest in farming among younger generations, the arduous nature of the work and all the costs of staying afloat, including property taxes, as reasons that farming numbers have declined. As for Black farmers, some observers, including the liberal leaning Center for American Progress, have said Black farming numbers have been hurt also by past discriminatory practices by lending institutions and federal agencies, including the USDA.

“There are a lot of reasons why the land is changing hands,” Cosby said.

But helping farmers retain their property is a USDA goal, Cosby said, adding that the five-year agricultural census helps shape federal policy to support the nation’s farmers. He urged farmers to contact their regional USDA office to learn more about resources available to them, including recent agency research findings in soil health sustainability -practices.

Cosby’s work with the agency also has included finding new ways and places to grow food.

He said that more people seem to be interested in starting home gardens, “especially now during this pandemic.”

“People have been getting creative,” he said, noting that personal food production is taking place in backyards, front yards, pots on patios and city rooftops. “You don’t need a lot of space to do this.”

Community gardens are also increasing in popularity, he noted. Besides offering a resource for growing produce, they provide space for people to get together and socialize, “to get to know their neighbors and to beautify the neighborhood.”

Meeting Community Needs

Yellow Springs resident Cheryl Smith, who also helped organize the 2020 conference, said that when she was growing up on the predominantly Black west side of Dayton, “almost every home had a garden — vegetable gardens, herb gardens, flower gardens.”

A longtime community activist, Smith said she sees the issues related to farming and food production through a social justice lens.

“It’s so important for us to meet the needs of the people,” she said in a telephone interview this week.

She noted that social justice action is often seen within an urban setting, but food production and access transcends urban and rural divides and ties communities together.

There is empowerment in having control over your own food sources, in “being the producer, not just the consumer,” Smith said.

Giving individuals and communities tools to support their own agricultural-related needs has been a focus of several recently implemented programs at Central State University, which will host tours of some of those efforts on Friday afternoon. An aquaphonics center, honeybee research, a botanical garden and plant research facilities will be presented.

Founded in 1890 as a land-grant institution, the historically black university’s land-grant status was renewed in 2014, resulting in new state funding related to agricultural and natural resources research and programming, according to the director of CSU’s extension efforts, Alcinda Folck, in a phone interview this week.

Her office’s focus is in sharing the university's research findings with “an underserved and under-represented audience” across the state, specifically minorities and veterans, Folck said.

The programming also serves students in opening avenues to careers in agriculture.

Clemens said he hopes more young people find the joys he’s experienced in farming. As an only child with no siblings, he worries about the future of his family’s land. He said he tries to encourage young people to try farming, but he’s been met with resistance from Black youth who tell him “it’s too close to slavery.”

For Clemens, the farming life is freedom.

“I’m working for myself,” he said. “I’m not working for any other man.”

More Local Stories By Elevate Dayton News